Dyslexia and foreign language learning

For individuals with dyslexia, learning to read and write in their mother tongue can be quite a challenge. When it comes time to learn modern foreign languages at school, many feel the ordeal of mastering literacy skills all over again is not worth the time and effort.

Depending on the country and school system, it may be possible for students with dyslexia to be released from the foreign language learning requirement. But there may also be some added benefits for dyslexic students who decide to pursue study of languages outside of English.

How successful they are depends on the individual student, the approach taken, and to some degree, the language students choose to learn.

What is dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a language based learning difficulty that affects reading and spelling abilities in a child’s mother tongue. While no two individuals with dyslexia will have the same symptoms, 75% of dyslexics struggle with breaking language into its component sounds. This makes it difficult to decode words, which is an essential part of early reading. It also makes it hard to spell and can affect working memory and processing speed.

That's not to say students with dyslexia are always at a disadvantage when it comes to language. On the contrary, they can have keen analytical skills, be very creative, and be good at thinking outside of the box and problem solving. These are all essential qualities when you are confronted with a new linguistic system and an unfamiliar grammar to map and explore.

Learn more about the strengths associated with dyslexia.

Language learning and dyslexia

Dyslexic students who study languages may have difficulties hearing sounds, connecting those sounds to letters, sounding out words and memorizing new vocabulary. They may also struggle more in reading and writing activities.

To improve literacy skills in their first language, it is sometimes recommended children with dyslexia “overlearn” words. This can help them recognize terms by sight, boost their reading skills and support them in becoming stronger spellers. The same applies in foreign language learning.

Additionally, it can help to take a phonological approach to learning. There is evidence that this approach is beneficial in second language learning even for people who do not have dyslexia.

That's because new phonemes that don’t exist in your native tongue will be harder to hear and produce. Babies are born with the ability to hear any sound, but by the time they are 1 year-old, their brains have been tuned to the language around them.

When you begin learning French or Spanish, you need time to become familiar with the most frequent sounds and sound combinations, so you can parse the speech.

Opaque vs. transparent languages

Not all modern foreign languages are created equal. Some, like French, Danish and even English, can be hard for students with dyslexia, while others like Spanish, German and Italian may be easier. What makes them more difficult is the “opaqueness” of the language, or how easy it is to break words up into their component sounds and how well those sounds match up to letters and letter combinations.

For example, it is sometimes said that Danish speakers swallow their consonants, making it tricky for learners to hear exactly which sounds have been uttered. Looking at a word on paper, you will not necessarily know how to pronounce it.

The same is true of French, a language in which je peux (I can), il peut (he can) and un peu (a little) are all pronounced in the same way (the –x and –t endings are silent) but mean different things.

There is also something to be said for a language being consistent in its approach to spelling. You won’t find spelling bees in Germany or Spain given spelling is so predictable. Unfortunately, this is not the case for English.

Dyslexic students and English language learners alike often struggle with irregular spelling in English and may need to develop an extensive repertoire of strategies in order to overcome these difficulties.

But what about languages that are written in a different direction, like Arabic?

And how about those that don’t have an alphabet, such as Mandarin? Learning Chinese entails matching meaning and sound to a specific character.

This uses a different part of the brain for processing than an alphabetic language and there have even been studies that show dyslexic students have fewer difficulties learning to read and write in character based tongues.

Hints & tips for dyslexic students

Start with speaking and listening.

Regardless of the presence of dyslexia, focusing on speaking from Day 1 will help you gain fluency in a language. How many times have you heard of people studying grammar and vocabulary for years at school but never feeling comfortable enough to hold a conversation? Don’t let that happen to you. Not only are speaking and listening skills easier for dyslexic students to learn, but they are the most useful skills if you plan on traveling abroad.

Focus on phonology.

Problems with reading and spelling are often a result of not being able to match sounds to letters accurately. A great way to develop this skill is to watch a foreign film with subtitles in the film’s original language. In this way, you are reinforcing your sound-letter mapping skills as you listen and read the foreign language. Don’t focus on understanding meaning in the beginning, they’ll be plenty of time to worry about that later.

Practice pronunciation.

Getting to know the sounds of a language shouldn’t be a passive affair. Download some recordings and tackle the individual phonemes. Don’t stop at word parts. Practice entire words and phrases too. Keep in mind that sounds often come out quite different in isolation vs. when they occur naturally in spoken language. If you are having trouble with a particular phoneme, look up YouTube videos to help you or try contacting a native speaker via a language exchange site.

Drill minimal pairs.

To train their ears to the new sounds, language students often study minimal pairs, which are words that differ by only one sound. This might also be helpful for dyslexic students who are taking a multi-sensory approach. A multi-sensory approach entails hearing words at the same time as you see them, and perhaps writing or typing them on a computer too.

Have the right kind of motivation.

Did you know there is more than one type of motivation? When you are motivated to learn a language in order to do better at school or get a promotion at work you are instrumentally motivated. However, the type of motivation that most correlates with success in language learning is integrative. This is when you take an interest in the people who speak the language you are studying. You can develop integrative motivation by meeting native speakers and discovering more about their history and culture.

Prioritize intelligibility vs. accuracy.

Mistakes are part of the process when it comes to learning a language. Even children mastering their first language have to go through plenty of U-shaped curves before they understand how a rule works and when to make exceptions (consider children learning the simple past in English and inventing words like maked, drinked, and taked). You don’t need to have perfect grammar in order to communicate. In the beginning, making yourself understood is what counts.

Surround yourself with language.

You might try leaving the radio on in a foreign language, listening to songs, news reports, or even formal lessons. The more language you are exposed to, the better your ears will get at parsing the speech. This is when you are able to hear where one word starts and stops. Without this skill, it is difficult to make sense of the language to which you are exposed.

You can use your knowledge of sound-letter mapping to write down the new words you hear and look them up in the dictionary (unless you’re learning English in which case the spelling can really throw you for a loop!). You can also label objects in your apartment and put up a few posters with foreign text. Train your brain to hold the foreign letters in working memory for longer and longer intervals to strengthen the visuospatial sketchpad of working memory.

Contextualize your learning.

Both dyslexic students and those individuals without learning difficulties will find it easier to acquire a new language when it is first met in context. In fact, much of what you eventually produce will be words you have acquired from the input to which you are exposed vs. explicitly studied. Context provides clues about meaning, form and function that you won’t get from a list of vocabulary.

Use the Keyword Method.

A mnemonic approach to learning vocabulary can help dyslexic students get the first 300-400 words into long-term memory. It entails finding a word in your native language that sounds like the target foreign word. If you can’t find just one, look for several. The most important factor is that both words start with the same sound. Next, create an anecdote and visualize it to connect the meaning of the word that sounds similar to the meaning of the foreign word.

Make flashcards for review.

Research on attrition shows that it’s easier to maintain your vocabulary if you review words at spaced intervals that are just right for your own personal forgetting curve. Many electronic flashcard programs today do this for you, just be sure they are adaptive and use a spaced repetition algorithm.

Ask your school for assistance.

Given the amount of challenges associated with language learning and dyslexia, it’s worth having a chat with your teacher and learning more about specific resources or even native speaker tutors that might be available to you. Adapting the method of instruction can make a big difference for dyslexic kids struggling with a foreign tongue.

For teachers looking for more tips on helping dyslexic students in the classroom, try this article.

Languages are hard

Don’t be discouraged and keep in mind that everyone struggles with their second language. One of the reasons why languages are so hard is you’re not just learning a language, you’re learning how to learn a language as well!

Memorizing words will be slow going in the beginning, but research shows that after a certain point (usually when you have learned between 300-500 words), the brain starts to recognize the similarities between these new data points and understands that they are part of a different system.

This is the so called “Eureka” moment when learning a language becomes easier as the brain creates a separate network for Spanish or Japanese and you can begin learning vocabulary via concepts instead of just first language equivalents. As the brain is a muscle, once it learns this process, setting up a network for your third, fourth or even fifth language is even easier!

The benefits of languages

Dyslexic students who are successful learning a foreign language often experience huge gains in self-confidence, which can extend to other areas of the classroom. Languages also present a great opportunity for them to strengthen cognitive skills, including working memory, and to express their creativity.

Research suggests bilinguals are dynamic thinkers, better problem solvers and even have more developed social skills. In older learners, acquiring a foreign tongue can also help to fight off dementia. This is because learning a language is about strengthening the brain vs. allowing it to atrophy.

Improving English literacy may help

Some researchers advise strengthening a dyslexic student’s phonological understanding of his or her mother tongue before taking on study of a foreign language.

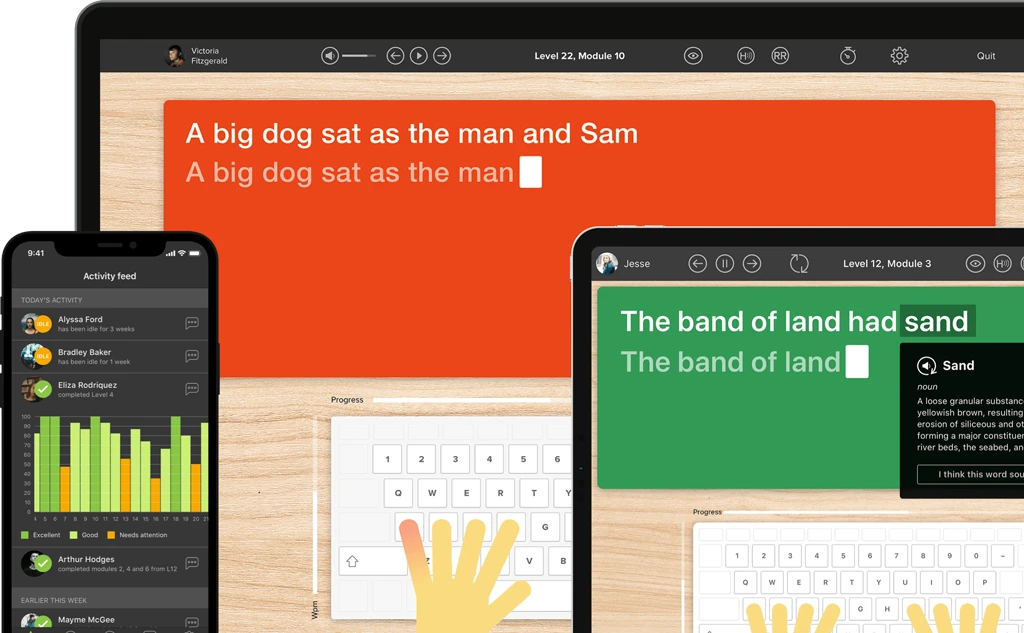

Touch-type Read and Spell is based on the Orton-Gillingham Approach and offers a multi-sensory and modular style of learning that has helped many students with dyslexia strengthen their English literacy skills.

Students learn at a pace that is right for them and gain a valuable skillset at the same time -- the ability to type without looking at the keyboard!

Being in control of their own learning and receiving plenty of positive feedback along the way helps them become more confident and self-efficacious about taking on a larger task and breaking it down into manageable steps.

And did you know that the skill that most correlates with success in foreign language learning is not motivation, but rather self-efficacy?

For learners who struggle with dyslexia

TTRS is a program designed to get children and adults with dyslexia touch-typing, with additional support for reading and spelling.

Chris Freeman

TTRS has a solution for you

An award-winning, multi-sensory course that teaches typing, reading and spelling

How does TTRS work?

Developed in line with language and education research

Teaches typing using a multi-sensory approach

The course is modular in design and easy to navigate

Includes school and personal interest subjects

Positive feedback and positive reinforcement

Reporting features help you monitor usage and progress