What does dyslexia mean to me?

A guest post by journalist David Hayter.

My life and livelihood are entirely dependent on those skills most severely affected by dyslexia. I work as a journalist: reading, writing, editing and organising are my passion, and they are the very things that I was told, as a child, that I would forever struggle with.

Rather than holding me back, receiving a dyslexia diagnosis at a young age not only helped me come to terms with and develop strategies to cope with my dyslexia, but to master the very skills that were the source of so much frustration and anxiety in my school years.

Childhood struggles: School, spelling and early symptoms

Dyslexia is not something that is easily understood by a child. Before I was diagnosed, I didn’t think I had a learning difficulty, like most children, I simply believed I was “bad at English” and hopeless when it came to spelling. Reading wasn’t quite as challenging, but every individual with dyslexia is unique.

Junior school would prove incredibly frustrating. I loved to write and read adventure stories, but when it came time to receive my marks, they were middling at best. Understanding and engaging with the material was easy, getting down my thoughts in coherent, let alone perfectly punctuated sentences was problematic, to say the least.

I quickly became accustomed to the same old refrain: “David is an incredibly creative and very bright child, he has such potential, but he struggles with sequencing, and his spelling isn’t up to snuff.”

Luckily for me, my parents and teachers suspected something that no eight-year-old possibly could, that my problems at school might be the result of a learning difficulty.

Recognizing the symptoms of dyslexia isn’t always easy. For more tips on spotting dyslexia symptoms in adults, try this article. If your child is struggling with reading and you suspect dyslexia, have a read through this article.

The importance of diagnosis

One sunny afternoon, I found myself plucked out of school and on my way to visit a lovely old lady in Tonbridge for, what seemed to me to be, a strangely irreverent chat about my studies and how I thought about my problems. I could not have known then, but that meeting and discussion focused on approach, as opposed to results, would go on to shape my entire ethos to thriving with dyslexia.

I later discovered that that strange afternoon was, in fact, an assessment with a child educational psychologist. My IQ and reading comprehension were being tested, but so was my potential for dyslexia. There was good news and bad news; my intellect and comprehension were excellent, while my structure and organizational skills would forever suffer.

Thankfully, rather than viewing my freshly diagnosed dyslexia as a setback, the experience of openly discussing both what I struggled with and what I excelled at would fundamentally change my attitude and the approach of my teachers.

Teachers and teaching methods

Make no mistake, telling a young boy he has dyslexia and is going to have to forgo the chance to run around with his friends at break time, so he can sit down with this teacher or that teacher and practise those dastardly speech sounds, is never going to go over well, but it makes a huge difference in the long run.

Suddenly my teachers went from barking, “you should know their from there and it’s from its by now Hayter,” to sitting down and taking the time to both explain where I was going wrong and listen to me as I articulated my struggles. As each teacher found unique ways to work with my dyslexia and engage my passion for learning, slowly but surely, I started to master those confusing words and sounds.

The change was truly transformative. Adults now understood I was not being obstinate, ignorant or lazy and, as a result, they tailored their approach to compensate for my weakness and showcase my strengths. I was granted a little extra time in exams so I could fully focus on the content of my essays without panicking about certain words or running out of time as I corrected my mistakes. I was given more time to read what I had written, something many people with dyslexia can benefit from.

Coping with adult dyslexia: University and a career in journalism

Of course, no amount of extra-classes or spelling and organizational exercises could negate the symptoms of dyslexia. They certainly helped, but to this very day, I can fire out a 2,500-word feature or transcribe an hour-long interview with a rock star and know that when I read my first draft, I will find it littered with little errors. This might sound dispiriting, but it’s this knowledge that turned my learning difficulty into a superpower.

No matter how infuriating it may be, dyslexia would not stop me from reading history and politics at university – even if that meant penning a daunting 15,000-word dissertation and planning presentations each week – and it would not stop me from becoming an editor – where it would be my responsibility to audit the work of colleagues with a fine-tooth comb.

Knowing and understanding the symptoms of dyslexia are key. I have come to accept that I will compose a carefully crafted article only to find that, for some inexplicable reason, I will have left the “ly” ending off of every adverb or somehow confused “see” and “sea” (or any number of other sound-alike words).

Somehow, somewhere, between my brain and my fingertips, these mistakes occur. I cannot account for it, and while I have minimized their occurrence, I have failed to eradicate them entirely. Instead, my entire ethos changed. Rather than getting bogged down by problems and trying to ensure every word in every sentence was perfect before moving on, I chose to focus on what I had always loved, the bigger picture: the joy of writing, the depth of analysis, the intricacies of argument and the art of constructing a narrative itself.

Understanding your dyslexia

Great writing and perfect spelling are not remotely interlinked. There is no greater shame than seeing a child give up or become discouraged because she is struggling to reconcile certain sounds with certain words. At a young age, dyslexia will always be an uphill battle, but the key is to understand and embrace your weaknesses while enjoying the subject matter itself.

As an adult, I know my dyslexia inside and out. I can predict the type of errors I’m likely to make, the words I may confuse and the endings I might omit. Rather than letting this knowledge bring me down, it instead grants me incredible freedom. I can focus on the language itself and the task at hand because I intrinsically understand where to look when I’m transforming my first draft into the finished article.

Deadlines might appear terrifying to some people but, because of my dyslexia, I’ve spent an entire lifetime racing against the clock to spot my own mistakes. So when I’m tasked with getting a detailed review or feature-length interview ready for publication within a matter of hours, it feels like second nature.

Turning a “weakness” into a strength

In fact, when I trained to become a journalist, something very surprising happened. I had to take a sub-editor’s examination. In theory, this should be absolutely terrifying for someone with dyslexia – an exam based around reading and correcting errors, putting things in order, organizing other people’s work and making sure that an entire publication is without fault. In other words: one giant two-hour test of my and every other dyslexic’s learning difficulties.

Suffice to say, even having graduated university with Distinction, I was dreading it. I had hoped that exams were a thing of the past. I had learned to master argument and analysis, the last thing I wanted was one big reminder of my dyslexia and my linguistic insecurities.

To my absolute shock, I not only passed my sub-editing exam, but I got top marks. It turns out I was even better at correcting errors than I was at writing articles or interpreting journalistic law. What’s more, when I sat the exam, it felt entirely natural. What should have been a nightmare ended up being, not only a breeze but something I genuinely enjoyed.

In my professional career, I have always relished the opportunity to be an editor: to correct errors, to organize a team of people and structure an entire week’s worth of carefully composed content. In fact, because I’ve spent so many years studying language, understanding my learning difficulties and focusing on how to write beautiful (if not always perfectly spelled) prose, it felt natural helping others.

To this day colleagues old and new ask me for advice, not because I am some sort of spelling ace who can write without flaws, but because I can patiently and sympathetically explain why a different approach or phrasing might prove more effective. In a strange way, I’ve taken on the role of all of those supportive adults from my childhood.

Being diagnosed with dyslexia as a child was not a stumbling block, it was a moment when my horizons broadened, and I embraced a new way of thinking that would reshape my entire life. Far from holding me back, the learning difficulty I faced as a child at school armed me with a set of skills and coping mechanisms for adults. It gave me the inside edge when it comes to facing challenges.

To this day, I make my way in life based entirely on the skills that I was once told I would never master.

Recommended strategies and coping mechanisms for dyslexia

- Don’t miss the forest for the trees. So many subjects at school and careers in life depend on reading and writing skills, but spelling and grammar are just a small part of a much bigger picture. If you or your child can engage with a subject conceptually, having a flair for argument, interpretation and understanding will serve you well in the long run. Don’t let dyslexia cause your head to drop.

- Understand your learning difficulty. Those early school years will be difficult at times, the marks won’t always be ideal, and it will feel like your teachers are repeating the same criticisms over and over and over again. Don’t worry, it will take time, but seek to understand and recognize the mistakes you happen to make. Some words will always cause problems, so be aware of them instead of letting this get you down.

- Your teacher matters. Having a teacher who understands your learning difficulty is pivotal. Adults sometimes fail to recognize the impact their words have on children. There is a profound difference between telling someone they are wrong until they (hopefully) get it right, and developing thoughtful strategies that engage a child’s specific needs.

- Don’t be discouraged by dyslexia. You will get things wrong, and you will make mistakes, but these problems are not the end of the world. There are people who are supposedly hopeless writers (with and without dyslexia) who are absolutely thriving in this world because talent and insight trump grammar. That is not an excuse to avoid honing those tricky skills; it’s a reason to be optimistic. Intelligence and opportunity are not limited by your learning difficulty.

For adult learners

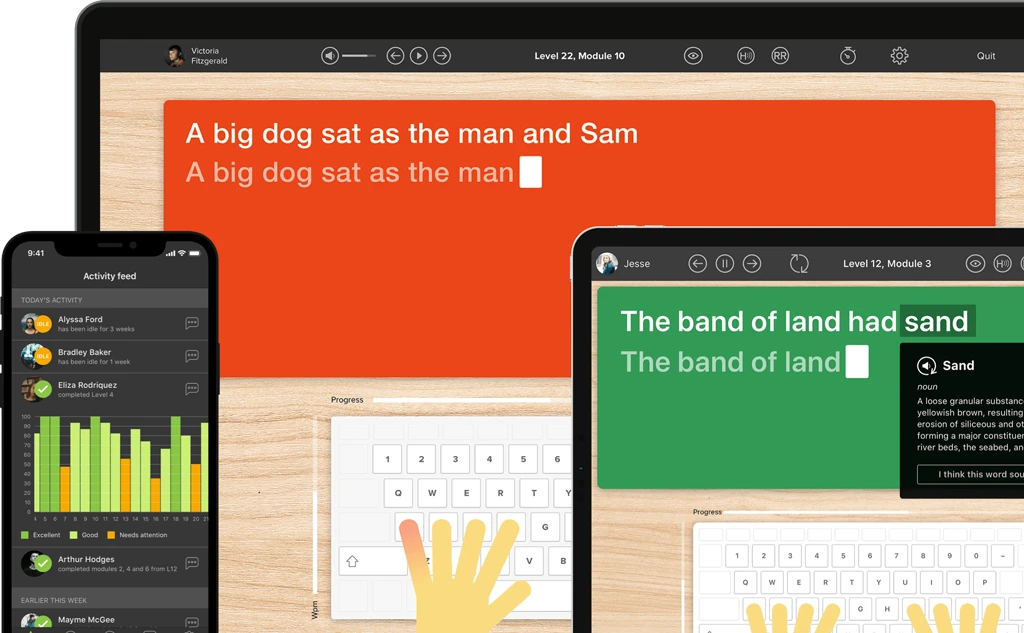

TTRS is a program designed to get adults with learning difficulties touch-typing, with additional support for reading and spelling.

Meredith Cicerchia

TTRS has a solution for you

An award-winning, multi-sensory course that teaches typing, reading and spelling

How does TTRS work?

Developed in line with language and education research

Teaches typing using a multi-sensory approach

The course is modular in design and easy to navigate

Includes school and personal interest subjects

Positive feedback and positive reinforcement

Reporting features help you monitor usage and progress