How common is functional illiteracy?

Functional illiteracy is different from illiteracy. Adults who are functionally illiterate have some reading and writing ability, whereas a person who is illiterate has never been taught how to read or write. Thanks to government regulations that make school attendance mandatory, there are fewer illiterate people today compared to in past centuries. However, functional illiteracy is more common than you might think.

Some estimates suggest that 1 in 7 people in the United States and the United Kingdom struggles with literacy skills. Functional illiteracy is defined by the extent to which difficulties with reading and writing prevent an adult from serving as a functioning member of society.

Literacy skills are the key to graduating high school, getting a job, pursuing further education, accessing job training and advancing in your career. You also need to be able to read and write in order to use a computer, send emails and text messages to friends and family, engage on social media, and navigate the web.

The 1 in 7 figure is based on a 2006 World Literacy Foundation report but does not tell the full story. That’s because reading ability can differ significantly from one person to another. Literacy skills are measured by test tasks with passages and questions that assess comprehension skills, such as the ability to extract details, understand the gist of a text, recognize inferences, and make predictions based on a reading.

How well an individual does will depend on previous education opportunities, the language he or she regularly comes into contact with, the complexity of the text, including how abstract it is and if it contains specialized vocabulary, and the context in which the content is encountered. When it comes to writing, some adults struggle with poor spelling while others are completely unable to express themselves in written English. There may also be a noticeable gap between the individual’s written and spoken vocabulary.

Learning difficulties and functional illiteracy

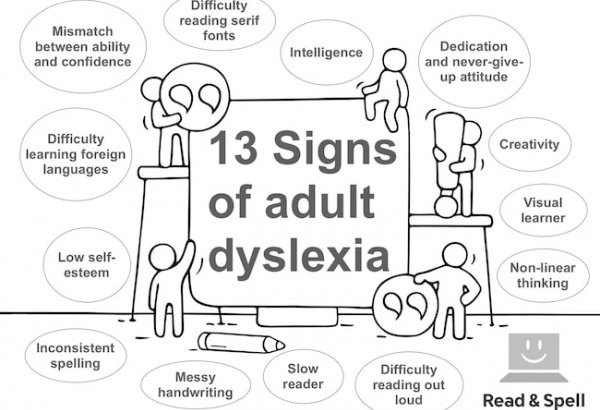

In certain cases of functional illiteracy, reading and writing skills were not developed during childhood because of an undiagnosed learning difficulty. Language-based specific learning differences like dyslexia can interrupt a person’s ability to split spoken language into its component sounds, which complicates reading and spelling efforts.

Dyspraxia is a motor skills disorder that makes writing by hand hard, and attention-based disorders such as ADD and ADHD make it challenging for an individual to focus on a task and sit-still for activities that develop literacy skills. When a Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLD) goes undiagnosed it can not only result in poor performance, but also cause low self-esteem, low confidence and avoidance of social activities that involve reading and writing.

The tragedy is that when individuals with SpLDs gain early access to the right classroom accommodations and strategy training, they can develop literacy skills alongside their peers and achieve their full potential in the classroom.

Learn more about undiagnosed learning difficulties in adults.

What’s involved in reading?

Sounding out words

One of the first things beginner readers learn is to associate letters with the sounds they represent. This process is known as “decoding” and is the opposite of “encoding,” or spelling.

In order for a reader to successfully decode a word, a number of things must happen. He or she needs to recognize the letters of the alphabet, know which sounds they represent, understand how to break words down into their component sounds and then bring all of this information together.

This is more challenging in English than in some languages because there are more sounds than there are letters. There’s also a lack of consistency in word spellings as so many English sounds are represented by more than one letter and/or letter combination.

Sight reading

The more frequently a word is encountered, the faster our brains will recognize it and eventually we can read it without having to sound it out. In fact, fluent readers sight read the majority of words they encounter and only sound out new or low-frequency vocabulary.

There are different approaches to teaching literacy skills and some include an emphasis on memorization of high frequency words. This facilitates comprehension and fluency by conserving cognitive resources for harder and less frequent words.

Learn about different approaches to teaching reading.

Adult basic skills

Helping an adult develop his or her literacy skills can be a rewarding experience. While some people prefer to volunteer, others undertake careers as adult basic skills instructors. A variety of programs exist at community colleges and libraries to help people get high school equivalent in the US and GCSE qualifications in the UK.

Training might also be provided in math, typing, computer skills, and general life skills, such as how to create a resume, fill out job applications and answer questions during an interview. Learn more about adult basic skills and volunteering to teach adults to read.

Teaching mature learners

Working with adults is not always as straightforward as teaching children. Here are some practices and ideas to consider.

Observation

Many adults with functional illiteracy have developed “faking skills” which allow them to use the context of a text to guess at the meaning of what they are reading. Teachers will try to help mature learners take a step back from this practice and encourage them to give sounding out individual words or sight reading a try, even if it exposes their vulnerabilities. One way they do this is by creating a safe and judgment-free learning environment.

Finding out what they know

When teaching children you can assume every student is starting with a relatively similar baseline. This is not the case with adults who may bring vastly different skill sets, abilities, and experiences that can impact their openness to a particular approach or ability to work on the same set of tasks.

Encouraging learners

Adults often struggle with insecurities that prevent them from taking risks and exposing their weaknesses. This means encouraging an adult is every bit as important as it is a child who is learning how to read for the first time.

Respect

Adults who are willing to go back to school to improve their reading, spelling and math skills are taking a big step, one that could lead to major improvements in their lives. But returning to school isn’t always easy, especially when it dredges up old insecurities and memories of past educational failures. The best teachers respect their learners and remind them of how proud they are by recognizing and praising effort and progress, no matter how small the achievement.

Flexibility

With younger learners the main focus is on education, but for an adult who is juggling family life and a career, studying and completing homework may not always be a priority. Flexibility may be required with arrival and departure times, missing class or not handing in work. Just remember adult learners are there because they choose to be.

Misconceptions

Instructors will be aware that some mature learners secretly believe that they are less intelligent than everyone else because of their reading ability. They may also believe that school is simply not a place for them as they have a history of educational failure. However, intelligence and reading ability are not related and almost anyone can overcome literacy challenges with the right support and training.

Support

Support may be in the form of lessons, guidance on using resources, or it could be emotional support. Functional illiteracy can make an individual feel frustrated and lead to feelings of inadequacy, embarrassment and shame. These negative emotions may be rooted in early childhood experiences but they can prevent individuals from making progress long into adulthood.

You’ll find more background and helpful tips in our articles on teaching adults to read, literacy skills for mature learners, and spelling for adults. You may also want to read through some of the sites featured in our top 5 Adult Literacy Blogs post for more ideas.

Self-study opportunities

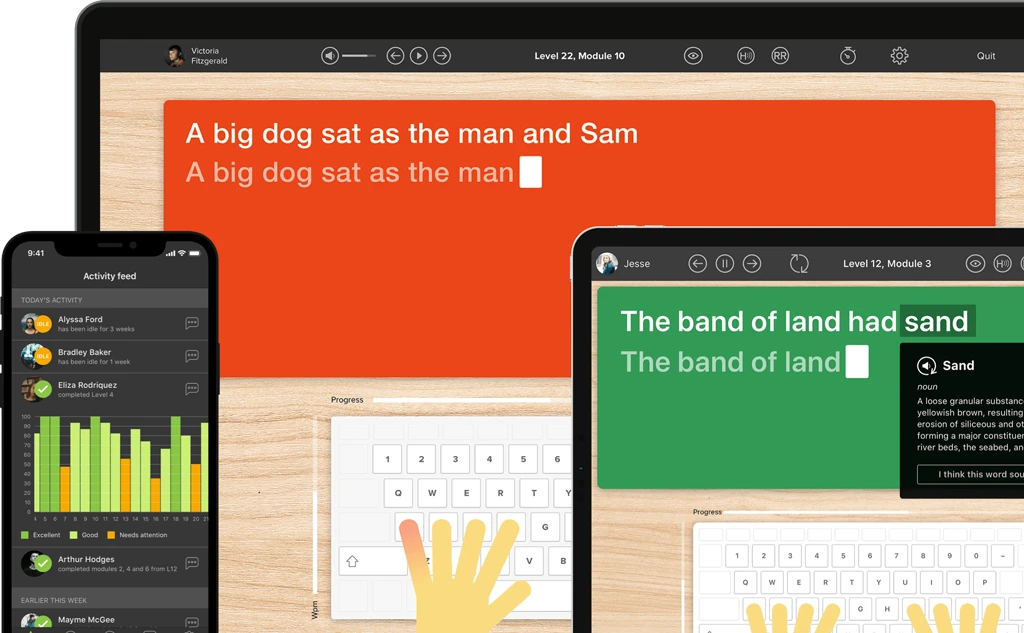

While teaching phonics and sight words face to face is extremely effective, sometimes a learner can benefit from online programs that help him or her practice skills independently and when a busy schedule permits. Touch-type Read and Spell is a flexible literacy focused solution that can be used during one-to-one tutoring, independently and in a small group setting.

It’s accessed online and teaches reading using a phonics-based wordlist that includes the most common sight words. Adults see words and sentences on the screen, hear them read aloud and type them with the correct fingers. This multi-sensory experience teaches decoding, sight-reading and spelling and at the end of the course gives working adults a new and valuable skill to add to their resume, touch-typing.

The multi-sensory and phonics-based approach makes it appropriate for adults with specific learning difficulties. What is particularly useful is that Touch-type Read and Spell is a typing course, this means it can be used by mature learners who are looking to improve their literacy skills without calling attention to any deficiencies.

Read more about touch-typing for dyslexics, the benefits of touch-typing, how long it takes to learn typing and job opportunities for typing.

For adult learners

TTRS is a program designed to get adults with learning difficulties touch-typing, with additional support for reading and spelling.

Chris Freeman

TTRS has a solution for you

An award-winning, multi-sensory course that teaches typing, reading and spelling

How does TTRS work?

Developed in line with language and education research

Teaches typing using a multi-sensory approach

The course is modular in design and easy to navigate

Includes school and personal interest subjects

Positive feedback and positive reinforcement

Reporting features help you monitor usage and progress